“Take it easy for a few days.” My doctor’s instructions were straightforward. I had just had a lumbar puncture and was supposed to chill out for 48 hours. “Getting enough sleep will help you recover. Rest when you feel tired,” explained the discharge summary. I understand the importance of sleep. Rest, however, is a more elusive concept. Does it refer to the mind, the body, or both? Put simply, what does it really mean to “take it easy?”

Research on rest is hard to come by because it is hard to pin down. Claudia Hammond, a psychology professor at the University of Sussex defines rest as “an activity that is restorative, intentional, relaxing.” In 2016, more than 18,000 people responded to a survey called The Rest Test which asked them how they unwind. The top answer was reading. Walking, taking a bath, and daydreaming were in the top ten.

Whether an activity is restful is in the eye of the beholder. For instance, reading might be a salve for one person but for a student preparing to sit for the Bar exam, it might be the exact opposite. Spinning class is my friend Marjorie’s favorite way to decompress. It is my version of hell.

Rethinking resilience

When we talk about mentally strong people, we typically focus on how productive and focused they are. As Shawn Achor and Michelle Gielan described in the Harvard Business Review:

We often take a militaristic, “tough” approach to resilience and grit. We imagine a Marine slogging through the mud, a boxer going one more round, or a football player picking himself up off the turf for one more play. We believe that the longer we tough it out, the tougher we are, and therefore the more successful we will be. However this entire conception is scientifically inaccurate. The very lack of a recovery period is dramatically holding back our collective ability to be resilient and successful.

Setting aside time to recover and rest might seem antithetical to modern life, but failing to do so can leave us emotionally and physically depleted. A recent article in The New Yorker entitled Why Are We So Bad At Getting Better? explores the perils of powering through instead of powering down:

After an infection, a surgery, or a panic attack, patients increasingly feel that they need “permission to recover,” and treat convalescence less as a chance to heal than as something to get over with. And, when we prize efficiency over recovery, we risk ending up with less of both.

I cannot help but think that bed rotting, the new trend sweeping TikTok which involves lounging in bed for extended periods of time—not to sleep but to do passive activities—is a reaction to the lack of downtime in our lives. Every once in a while, it’s possible that bed rotting might be restorative but I would caution against it as a go-to strategy to unwind. While lounging in bed all weekend may sound appealing at the end of a long work week, people often say they feel even more drained when they spend their time in mind-numbing passive activities. While lounging in bed may be just what the doctor ordered when recovering from illness or a surgical procedure, I do not think of it as an example of “an activity that is restorative, intentional, relaxing.”

What are you waiting for?

Many of us look to weekends, vacations and holidays as the best chance to recover from the daily grind but research shows that if we want to feel better, building regular downtime into our everyday lives is a more effective strategy. People tend to postpone breaks as a reward for when a task is complete but studies show that incorporating regular “microbreaks” (10 minutes is enough) from demanding activities restores vigor and reduces fatigue. The key is to completely detach from the work you are doing and to engage in a revitalizing activity. Note to self: that does not mean scrolling through social media.

Here are 6 ways to find rest every day:

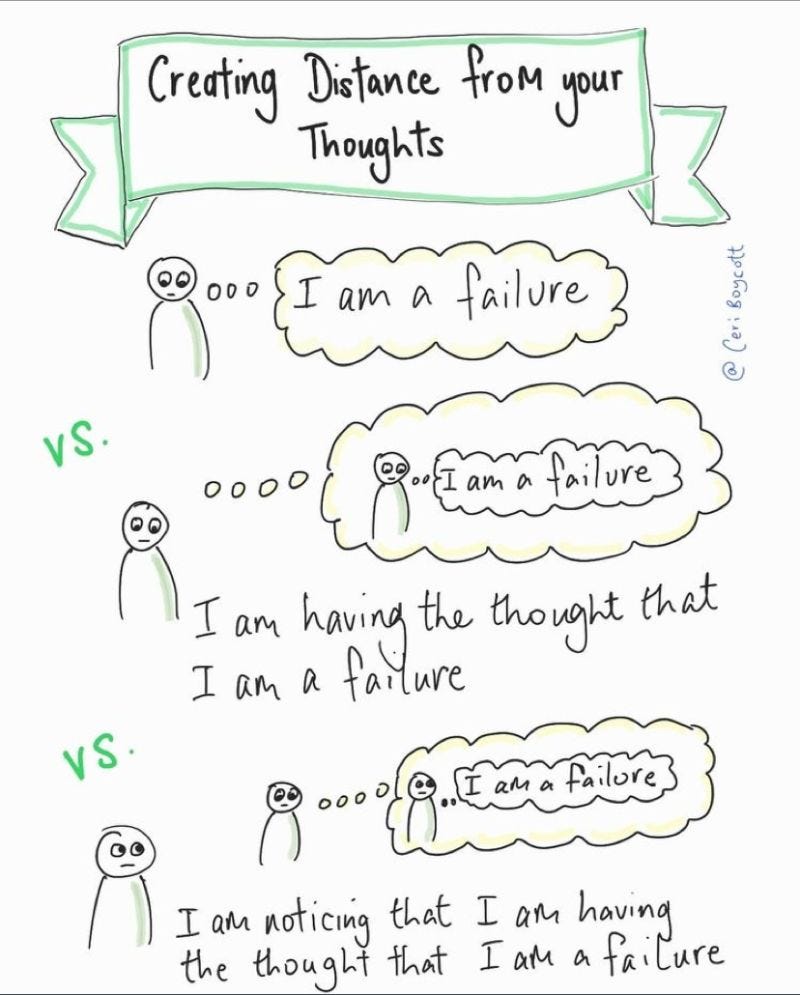

1. DETACH. Distance yourself from negative and stressful thoughts

2. RELAX. Take time to chill out and get away from the task at hand

3. DECIDE. Be deliberate about how you spend your time

4. EXPAND. Stretch your mind or body

5. ADD VALUE. Do something that is personally meaningful

6. CONNECT. Engage deeply with others

All too often we misjudge what will replenish us or fortify us. There is a lot we can’t control in our lives but we can be deliberate about how we spend our downtime. I recommend choosing activities that oxygenate the mind and body.

Bottom Line: Every day may not be relaxing, but try to find micro-moments to relax every day.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman