Suppressing negative thoughts might improve mental health. This isn’t a typo. Nor is it a lingering belief from my WASPY upbringing. It’s the findings of a new study published in Science entitled Improving mental health by training the suppression of unwanted thoughts. Contrary to accepted narratives about mental health, researchers from the University of Cambridge found that a stiff upper lip may have mental health benefits.

Father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud observed, “Unexpressed emotions will never die. They are buried alive and will come forth later in uglier ways.”

Author of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma Bessel van der Kolk has a similar take on taping down emotions, “As long as you keep secrets and suppress information, you are fundamentally at war with yourself.”

A counterintuitive approach

But what if assuming that talking about negative emotions and dredging up miserable experiences from the past is the only way to rob them of their power is misguided? What if ignoring certain thoughts isn’t maladaptive but can actually be a healthy coping strategy?

Researchers at the Medical Research Council (MRC) Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit in the UK trained 120 volunteers from 16 countries to suppress thoughts and worries about negative events. They found that not only did these thoughts become less vivid, they were also less anxiety provoking. Moreover, participants reported thinking about these feared events less. Counter to conventional wisdom, there was no paradoxical increase in fear or rebound anxiety. Furthermore, participants who continued to practice the thought-suppression technique continued to experience mental health benefits. Of note, many of the participants in the study had serious mental health issues including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

In Winter Notes on Summer Impressions, Fyodor Dostoevsky famously wrote “Try to pose for yourself this task: not to think of a polar bear, and you will see that the cursed thing will come to mind every minute.” The more we try to ignore polar bears and pink elephants, the thinking goes, the more they occupy emotional real estate. Harvard psychologist professor Daniel Wegner, PhD termed this phenomenon “ironic process theory.” Wegner theorized that when we try not to think of something, one part of our mind successfully avoids the forbidden thought, but another part “checks in” every so often to make sure that the thought is not coming up—therefore, ironically, bringing it to mind.

The good news is that ignoring pink elephants and bears might be easier than Wegner originally thought. A study published in Psychological Science entitled Taming the White Bear found that learning to ignore things is a powerful tool for helping people focus.

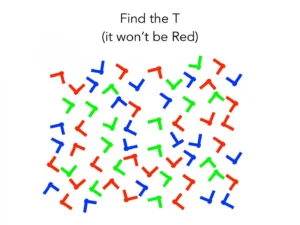

Here is the task participants were given:

Knowing what to look for is obviously important. The researchers also found that learning what not to look for matters too. Participants who were told what to ignore were more efficient at the task. This study highlights a key point about attention. The reason we’re able to focus on something is not just because of the attention we’re giving it but also because of our brain’s ability to block out other competing stimuli.

While searching for “Ts” and taming white bears might be easier than previously thought, these findings have application in the real world.

If you want to ignore something, here are three strategies to consider:

1. Be Deliberate

Going about your business while passively trying to ignore what’s on your mind is unlikely to work. Stop and acknowledge what’s bothering you and make a concerted effort to block it out.

2. Distract Yourself

Choosing a powerful and absorbing diversion can help you block out the unwanted white bear. Focusing on something else or someone else will help you tune out the rest.

3. Schedule Worry Time

Some research has found that asking people to simply set aside half an hour a day for worrying allows them to avoid worrying during the rest of their day. Next time an unwanted thought comes up, just try to tell yourself, “I’m not going to think about that until next Wednesday afternoon.”

Learning to selectively look the other way can help us see more clearly.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman