When someone is going through a rough patch, the typical recommendation is that they speak to a professional about what is bothering them. Articulating one’s feelings and challenging negative thought patterns, the thinking goes, is the best way to help an individual manage stress. A study published in The Journal of Positive Psychology turns this assumption on its head. Rather than focusing on an individual’s issues, the findings suggest that the best medicine for feeling down is doing something for someone else.

The study involved 122 people who had moderate to severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Participants were split into three groups. Two of the groups were assigned classic cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions: either planning social activities (Group 1) or cognitive reappraisal (Group 2). The third group was instructed to perform three acts of kindness a day for two days out of the week. Acts of kindness were defined as “big or small acts that benefit others or make others happy.” Participant autonomy was emphasized. When, where, and for whom they completed the activities was completely up to them. Examples of acts of kindness participated later reported included giving someone a ride or baking cookies for a friend.

The good news is that everyone in the study got better.

At the 10 week mark, all three groups showed an increase in life satisfaction and a reduction of depression and anxiety symptoms but those who engaged in acts of kindness experienced the biggest boost. Moreover, this strategy showed a clear advantage over the other two CBT-based interventions in feelings of connectedness with others, “Social connection is one of the ingredients of life most strongly associated with well-being. Performing acts of kindness seems to be one of the best ways to promote those connections,” explained David Cregg, co-author of the study. It is worth noting that simply planning social activities (Group 1) was not enough to make people feel connected. There is something uniquely beneficial about performing acts of kindness that makes people feel that they are part of something larger than themselves.

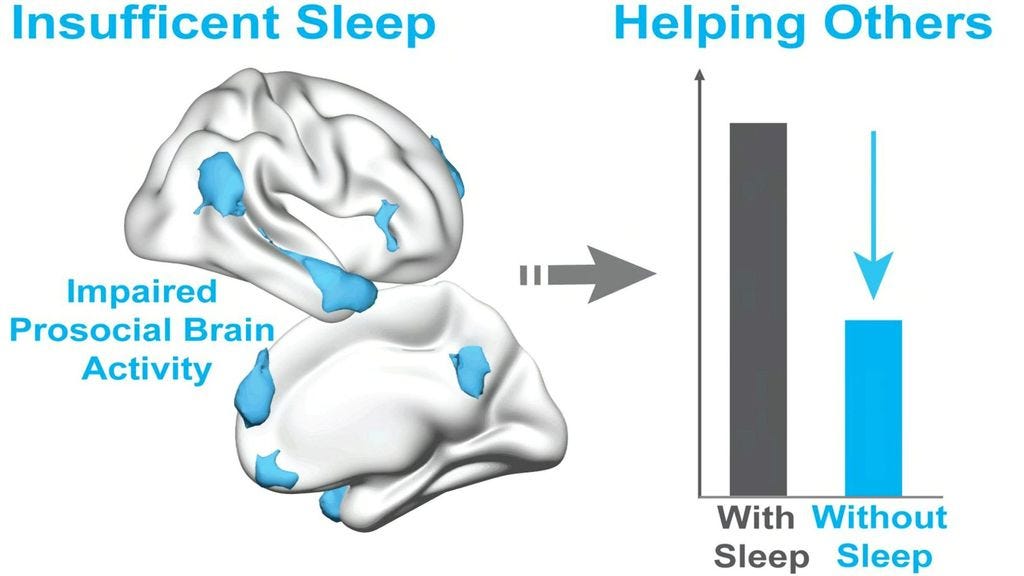

The research also revealed why performing acts of kindness was so effective: it helped people take their minds off their own depression and anxiety symptoms.

It turns out that doing good deeds reduces self-absorption which often manifests during stressful periods. We often assume that people who are feeling sad or anxious have enough on their plate. The last thing we want to do is burden them with helping someone else. The results of this study suggest that our intuition is misguided. Doing nice things for people and focusing on the needs of others may actually help people with depression and anxiety feel better about themselves.

“We do ourselves the most good doing something for others” — Horace Mann

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman