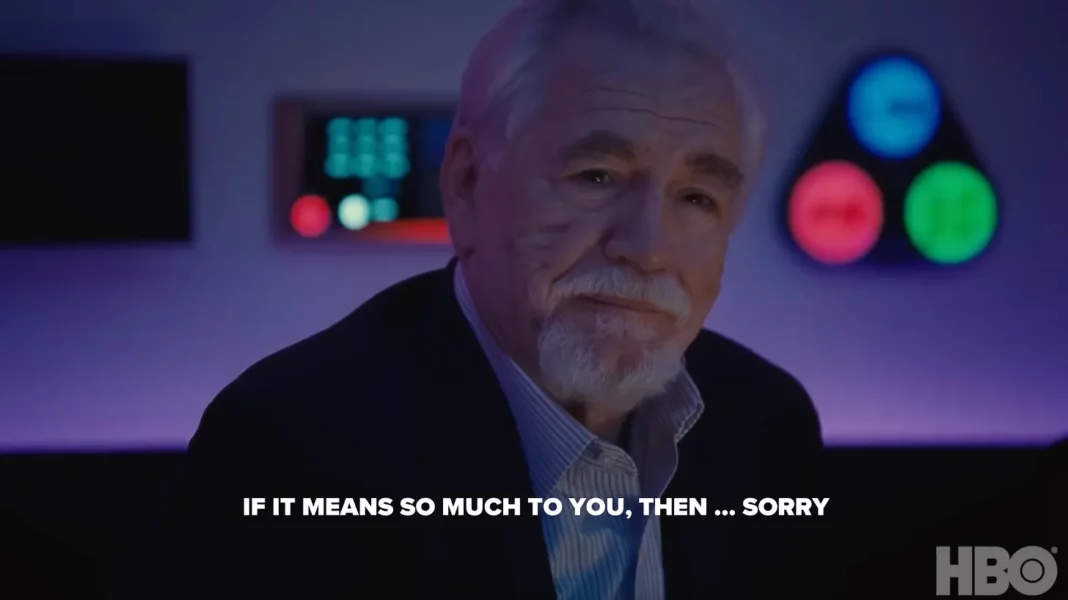

“If it means so much to you, then … sorry.” Logan Roy’s apology to his children in episode 2 of the fourth season of Succession is a masterclass in How Not To Apologize. In Logan’s defense, apologies are hard. They often get stuck in our throat or come out the wrong way. Even well intended apologies don’t always land well. As Randy Pausch, author of The Last Lecture said: A good apology is like an antibiotic. A bad apology is like rubbing salt in the wound.

At risk of sounding like a junior version of Logan Roy, I vividly remember being 8 years old and being forced to apologize to another child in the playground. “I’m sorry I took the ball but you were being a ball hog.” Alas, amends were not made and my nanny took me home. An explanation or justification is unlikely to promote resolution, or as Benjamin Franklin cautioned, “never ruin an apology with an excuse.”

When it comes to issuing an apology, acknowledging wrongdoing is key. Saying a version of “I am sorry if you were offended” shirks responsibility and basically blames the other person for being overly sensitive. Similarly, “Oops, my bad” is unlikely to resolve a conflict. So is “You have to forgive me,” as Carrie pleaded to Aidan after cheating on him in Sex and the City.

While there isn’t a formula for a good apology, there are certain factors according to research that make one effective including:

- Using the actual words “I am sorry” or “I apologize”

- Naming the offense — i.e. saying specifically what you are sorry for

- Taking responsibility and accepting fault

- Empathizing with the other person

- Conveying emotion such as regret or remorse

- Expressing a desire and willingness to make things right

Sincerity is essential. Even if the words aren’t perfect, if given from the heart and with good intention, a genuine apology shows the person that you care about them and about making amends.

Cartoonist Lynn Johnston described an apology as “the superglue of life because it can repair almost anything.” While an apology cannot right a wrong, it can begin the process towards reconciliation. Perhaps Elmer’s glue and Scotch tape are better analogies than superglue. From a joke that was unintentionally hurtful to more serious situations, saying “I’m sorry” matters. Forty percent of patients say they would not have filed a lawsuit against their doctor if they had received a proper apology and yet we often choose to skip them.

Of course, there are many reasons people don’t apologize.

For starters, we are highly motivated to maintain a positive self-image. Apologizing requires acknowledging wrongdoing. It’s a whole lot easier to justify our actions and minimize the harm we caused than to take responsibility. Perhaps this explains why some people, like Logan Roy, just “don’t do apologies.” Another barrier to saying “I’m sorry” is that we underestimate the positive impact it will have on the other person and also on ourselves. It’s helpful to keep in mind that apologies are less about changing the past than helping shape a less angry and more connected future.

It might be hard to apologize but at the end of the day, we all long to be forgiven, even Logan Roy. A short story by Ernest Hemingway entitled “The Capital of the World” captures this human need. It’s about a father and his rebellious son, Paco. The two had become estranged and Paco was living on the streets of Madrid. In an effort to repair the rift, the father took out an ad in a local newspaper that said “Paco, meet me at the Hotel Montana at noon on Tuesday. All is forgiven!” On Tuesday, 800 young men named Paco showed up at the hotel, looking for forgiveness.

I heard that story in church one day and it reminded me of palliative care physician Ira Byock’s observation that at the end of life, the wish to be forgiven is the chief desire of almost every human being. If we ultimately hope to be forgiven, apologizing is a good place to start.

That said…

While apologizing does not come easily to some, it comes too easily for others. When someone steps on my foot, I am the first to say, “I’m sorry.” I apologize for the weather, for terrible traffic, the long line at CVS and dozens of other undesirable situations that I am not responsible for.

I am not the only one who is inflicted with “Sorry Syndrome.” Many of my patients, especially women, tell me they insert “Sorry” into any sentence that contains a request.

“Sorry, may I have a glass of water?”

“Sorry, can I ask a question?”

“Sorry, where is the bathroom?”

Knowing how to apologize for something you regret is one thing. Apologizing for basically existing is another. As columnist Jessica Bennett writes:

Sorry is a crutch — a tyrannical lady-crutch. It’s a space filler, a hedge, a way to politely ask for something without offending, to appear “soft” while making a demand.

So why do we insist on apologizing for no reason?

A Harvard Business School study provides a possible explanation. According to the research, superfluous apologies build trust. In the study, an actor approached strangers in a train station on a rainy day and requested to borrow their phone. Half of the time, the actor prefaced his request with “I’m sorry about the rain!” The other half of the time, the actor went straight to the point and asked, “Can I borrow your cell phone?” Apologizing for the rain made a big difference: forty-seven percent of strangers offered their phone if the actor apologized for the rain. Only nine percent did without the apology. As the authors conclude:

Superfluous apologies represent a powerful and easy-to-use tool for social influence. Even in the absence of culpability, individuals can increase trust and liking by saying ‘I’m sorry’ — even if they are merely ‘sorry’ about the rain.

Building trust is important but does not justify apologizing for every little thing. If you want to reduce the number of superfluous apologies that roll off your tongue, consider replacing “sorry” with “thank you.”

For example, instead of saying, “Sorry for rambling” you can say “Thank you for listening.” Instead of saying “Sorry” when you move past someone on a train, you can say “Thank you for making room.”

An article in The Atlantic highlights the benefits of replacing an apology with gratitude:

“Sorry you had to do that” is not only a rejection of their nice gesture, a lot of times, it makes it weird. “Thank you for doing that” is recognizing and accepting their kindness.

Bottom Line: Save your apologies for when you have hurt someone and thank you for reading this article.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman