What makes you tick?

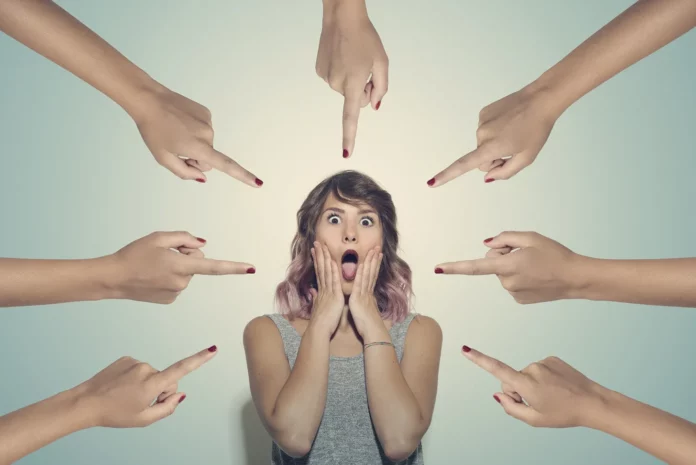

This is the question that drew me to psychiatry in the first place. What interested me most was not what people did but why they did it. What I have learned along the way is that there is so much that we get wrong about others. All too often, in an attempt to make sense of someone else’s behavior, we jump to conclusions about their “true self.” Using a few breadcrumbs of information, we are quick to make assumptions and attribute their behavior to a fixed aspect of their personality. The person who cut me off in traffic is surely a jerk. The woman who screams at her child lacks patience. The teenager who breaks the vase is clumsy. The dog owner who doesn’t pick up her dog’s poop is selfish. The coworker who leaves early is lazy.

Put simply, we see other people’s behavior as a reflection of who they really are. This is known as “correspondence bias”— we assume that their actions correspond to their personality. In doing so, we disregard all the other reasons that might explain their actions. In the process, we underestimate their intentions and the situation. We ignore external factors and contributing circumstances.

But, when it comes to ourselves, we do the complete opposite—we attribute our behavior to the situation and discount the role of personality. If I cut someone off in traffic, it’s because I am late for an important meeting. If I scream at my daughter, it is because I didn’t sleep well last night and she said something inappropriate. If I break a vase, it’s an accident. If I don’t pick up after my dog, it’s because I ran out of poop bags. If I leave work early, it’s because I have a doctor’s appointment. The only reason my behavior is anything less than stellar is because of external reasons.

We are quick to make excuses for ourselves but tend not to extend the same generosity to others.

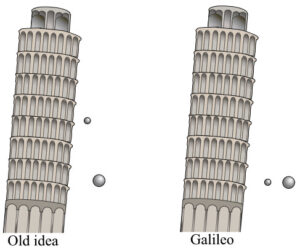

Psychologist Kurt Lewin likened this tendency to think that others are as they act to Aristotle’s understanding of the physical world. Aristotle believed that objects behaved according to their inherent properties. Rocks fell to the ground to get closer to the earth and flames rose to the sky to reach heaven. Accordingly, Aristotelian physics held that the heaver an object, the faster it would fall. It wasn’t until Galileo came along centuries later that the role of external forces was considered. His insight that the behavior of objects must be understood in the context of the situation transformed physics. It is said that he demonstrated the role of air resistance by dropping objects from the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

When it comes to judging the behavior of others, we are stuck in an Aristotelian mode—ready to make assumptions about their true nature based on a few observations and limited information. But in explaining our own behavior, we are Galileans—full of understanding and awareness of external factors.

Thanks to correspondence bias, we jump to conclusions and are left with the false impression that we really know someone, that we’ve got their number, for better or for worse. As Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert points out in a famous paper on the topic:

We may strive to see others as they really are, but all too often the charlatan wins our praise and the altruist our scorn. Juries misjudge defendants, voters misjudge candidates, lovers misjudge each other, and, as a consequence, the innocent are executed, the incompetent are elected, and the ignoble are embraced.

Correspondence bias is famously hard to overcome.

Even when we’re fully aware of the outside pressures that people face, we still understand their behavior as a reflection of enduring qualities. In a well known experiment, subjects were shown essays that opposed or supported Cuba’s president, Fidel Castro. Even when the subjects were told that the essayists had been instructed by a debate coach to defend a particular point of view, many of the subjects still inferred pro-Castro leanings in the essayists that defended him. As Gilbert observes, the subjects were basically saying:

“Well, yes, I know he was merely completing the assignment given him by his debate coach, but to some degree I think he personally agrees what he wrote.”

Correspondence bias is problematic because it distorts judgments and leads to misunderstandings. I worry that the rise of everyday use “therapyspeak”—prescriptive language describing certain psychological concepts—amplifies correspondence bias. Based on a tidbit of information or unpleasant interaction, we can justify writing someone off as “toxic” or “demanding.” Connections and potential connections suffer as a result.

Jumping to conclusions about what makes someone tick gets us nowhere. What we can do is simple: give everyone you meet the benefit of the doubt. Consider their intent. Resist wound collecting. Think about what else might be going on in their lives. Last but not least, ask yourself, “What would Galileo say?”

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman