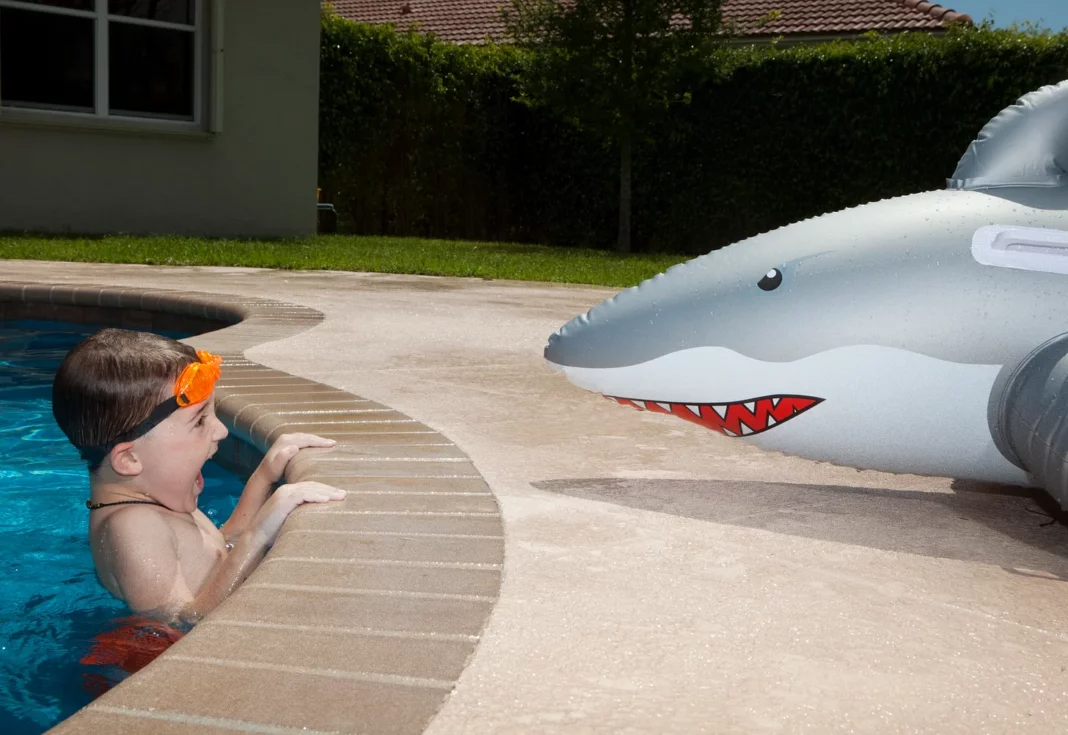

After all these years, the movie Jaws still haunts me. I love to swim in the ocean but lurking in the back of my mind is the possibility of a man-eating monster lurking just below the surface. Apparently, I am not the only one. According to a survey, 43 percent of people who have seen Jaws have lingering fears of the ocean.

Consider the following:

- You have a 1 in 63 chance of dying from the flu and a 1 in 3,700,000 chance of being killed by a shark.

- Over 17,000 people die from falls each year. That’s a 1 in 218 chance over your lifetime, compared to 1 in 3,700,000 of being killed by a shark.

- In 1996, toilets injured 43,000 Americans. Yes, it is more likely I will come face to face with a hostile toilet bowl than with an angry shark.

Sharks inspire terror but the mosquito should make our knees quiver. No other species, including our own, is responsible for the loss of as many human lives each year as mosquitos that kill 725,000 people annually. Humans murder around 475,000 other people each year. Snakes kill around 50,000 while dogs (mainly from rabies) claim another 25,000 lives. Some of the most feared animal (sharks, wolves) kill fewer than 10.

When it comes to fear, logic and reason fly out the window. Barry Schwartz explains:

People have great difficulty understanding risks. The weight a person gives to a scenario—flood, fire, winning the lottery—should depend on its likelihood. In fact, it depends on how easily it can be envisaged. People will pay more for air-travel insurance against “terrorist acts” than against death from “all possible causes.”

That said, fear serves an important function.

It alerts us to danger and enables us to act quickly. Think of swerving out of the way of an oncoming truck—you turn the steering wheel before you even register you are afraid. It is instinctive.

We see this all the time in the animal kingdom. When a gazelle is chased by a lion, her body goes into survival mode—stress hormones flood the bloodstream, the heart goes into overdrive, extra blood is shunted to muscles to facilitate running, awareness intensifies and vision sharpens as the body devotes all its energy to escaping the beast. If the gazelle outruns the lion and survives, she returns to the watering hole with her fellow gazelles and resumes her routine hanging out and eating grass. Stress hormones return to normal, along with blood pressure and heart rate. She doesn’t dwell on how upsetting it was to be chased by a lion, nor does the fear of another attack consume her.

People are not like gazelles. Problems arise when we are in fight or flight mode all the time. It isn’t quite as easy for us to flip back into relaxation mode. Those with chronic stress and anxiety experience the equivalent of the lion chase throughout the day, placing them at risk for a number of mental and physical problems.

My advice:

- Ask yourself: what are the odds of this terrible thing really happening?

- Know what you can control and what you cannot.

- Personalize a strategy to calm your mind. Meditation, exercise, listening to music, spending time outdoors, reading a book, visiting a museum, spending time with friends, volunteering, and cooking are all examples of ways to quiet an unquiet mind.

Find the one that works for you to channel your inner gazelle.

Bottom Line: Remember, FEAR has two meanings. Forget Everything And Run or Face Everything And Rise. The choice is yours.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman