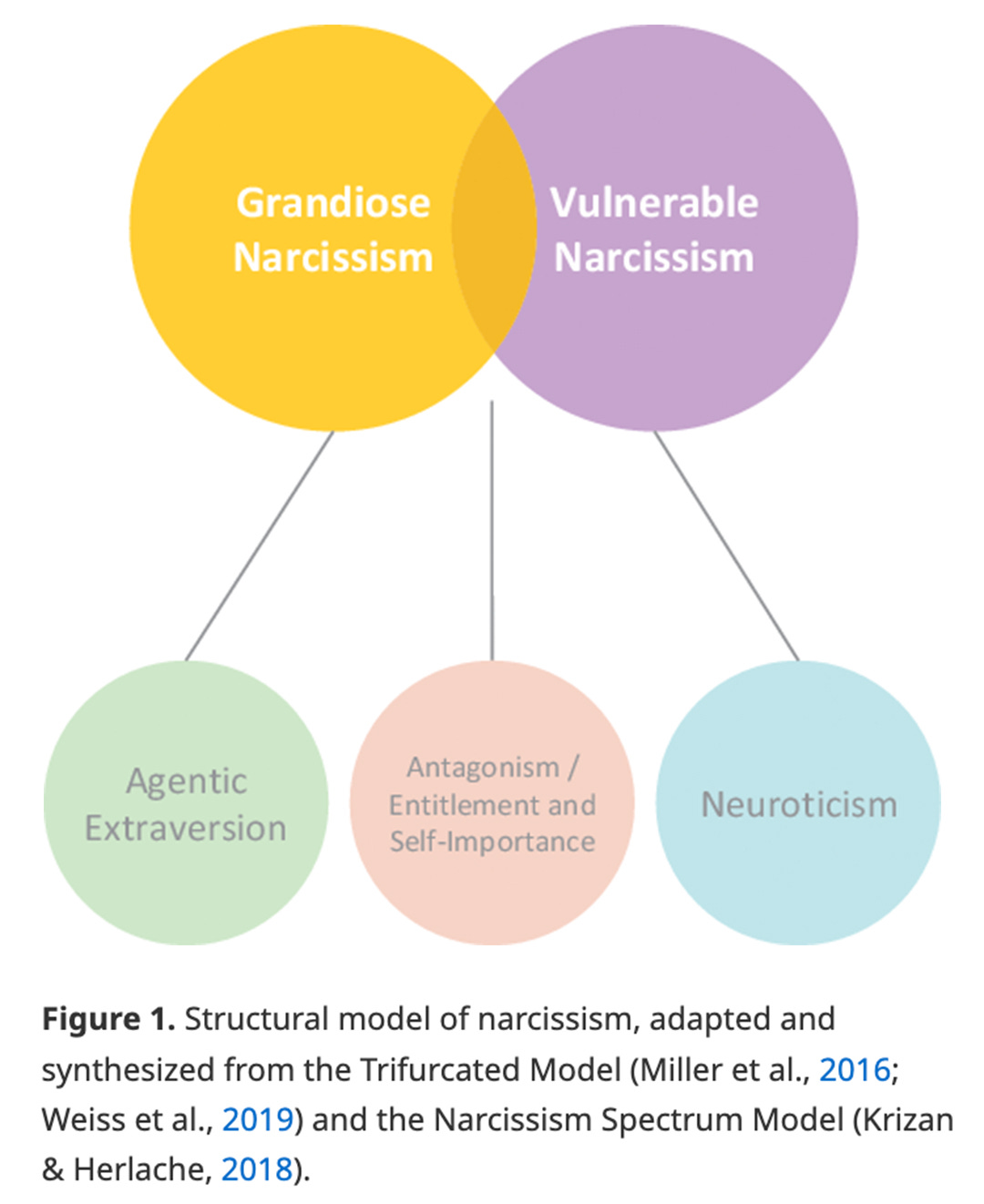

Vulnerable narcissists, also known as covert narcissists, may not be as overtly obnoxious or arrogant as grandiose narcissists but possess their own unique set of unappealing and noxious behaviors. Vulnerable narcissism is broadly defined in terms of hypersensitivity to rejection, negative affectivity, social isolation, but also distrust of others and increased levels of anger and hostility. As I have written about before, vulnerable narcissists swim in a sea of exasperated disappointment. “If only everyone wasn’t so incompetent” is their inner monologue. Finger pointing comes naturally to a vulnerable narcissist and they love to rehash the past and romanticize how much better things could be if only people appreciated them more. They are excellent at finding fault in others but oblivious to their own. Grievance collecting is their full time job.

A study published in the journal Personality and Individual Differences reveals some additional interesting underlying tendencies and motivations of these individuals. Specifically, it sheds light on how vulnerable narcissists experience laughter and teasing in daily life.

According to the researchers, there are three basic ways humor manifests in interpersonal contexts (and no, they have nothing to do with Italian ice cream):

1. Gelotophobia

This is the fear of being laughed at in social situations. People with gelotophobia tend to misinterpret laughter as malicious and assume they are the target of mockery, which then triggers distrustful emotions and social withdrawal. In their mind, laughter is ridicule. When they see people laughing, they assume people are laughing at them, not with them. Not surprisingly, gelotophobia is negatively associated with relationship satisfaction as it leads to the avoidance of intimacy in which they would feel exposed, vulnerable, or potentially ridiculed.

2. Gelotophilia

Gelotophilia is the opposite of gelotophobia — it entails the joy of being laughed at. These individuals experience being laughed at as a sign of appreciation, social connection, and shared humor. Not surprisingly, we are drawn to the people who roll with the punches and don’t take themselves too seriously. Life is a lot funnier when we have the ability to make fun of our own absurd existence. As the old saying goes, “One who laughs at themselves never runs out of things to laugh at.”

3. Katagelasticism

Katagelasticism refers to the joy of laughing at others. These individuals derive immense pleasure from making fun of and mocking people. They enjoy putting others down and exploiting their mishaps. They howl with laughter when someone makes a mistake or says the wrong thing. These are the people who become giddy when someone trips or makes a social faux pas.

Bottom Line: Take note of what people laugh at. It tells you a lot about who they are.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman