“There were many terrible things in my life and most of them never happened.” — Michael Montaigne

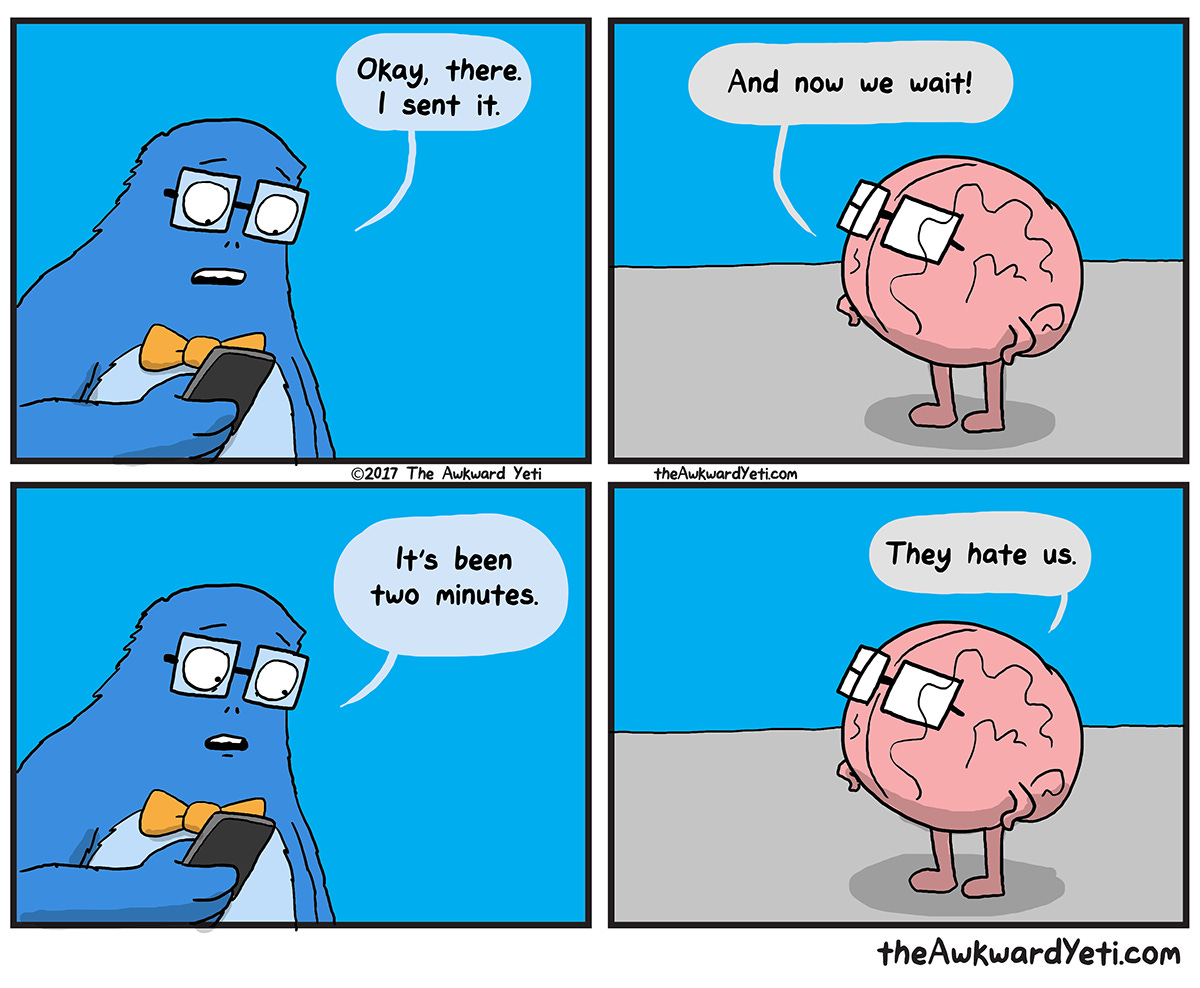

Here is why it’s bad for you: Negative Spiraling

When we catastrophize, we fixate on the worst possible outcome and treat it as likely, even when it is not. Overestimating the probability of a negative situation fuels irrational worry and turns a minor setback into a definitive dead-end. The result is hopelessness, frustration, and avoidance. The ultimate result of catastrophizing is missing out on opportunities and experiences that bring us joy and meaning.

Here is what you can do about it: Find Middle Ground

To counteract this doomsday mindset, Martin Seligman, the founder of Positive Psychology, suggests a simple exercise called “Put it in Perspective.” As soon as negative spiraling kicks in:

Step 1: Play out the worst-case scenario

Step 2: Play out the best-case scenario

Step 3: Consider what’s most likely to happen

Between the two extremes, you’re more likely to find the most realistic outcome.

As this exercise helps us understand, it is not the incident itself but the negative interpretation of the incident that leads to catastrophic thinking and the subsequent snowballing of negative emotions. The key is to un-twist these cognitive distortions and recognize that the mountain we face may in fact be a molehill or at least more of a Mount Pleasant than Mount Everest.

This isn’t toxic positivity. It’s deliberate optimism.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman