Mike, 41, came to see me after splitting up with his girlfriend. It was the fourth relationship in five years that had gone wrong. He was frustrated. “Why do I keep making the same mistake over and over again?” he asked.

He declared he was ready to move on. “What’s the point of dwelling on it? What’s done is done.” He described himself as an expert in moving on. “Isn’t that healthy?” he continued. Well, yes and no.

Mike, like many people I meet, was good at rationalizing what had happened. “She wasn’t right for me in the first place.” “She had a really annoying laugh.” “She didn’t love sports as much as I do.” Making excuses about why the relationship didn’t work out was easier than focusing on how sad he was about it. Rationalizing what went wrong in the wake of a failure or disappointment is a common response. It protects us from dealing with unpleasant emotions and feeling badly about ourselves. It also helps justify our behavior.

A student gets a C on a paper and dismisses the bad grade as not mattering all that much. An employee receives negative feedback on a presentation and blames the client and convinces themselves they will do better next time. These self-protective measures enable us to get past disappointment, but do we learn from them?

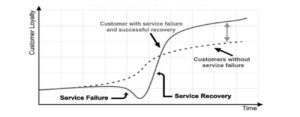

Instead of sweeping discomfort under the proverbial rug, the best way to overcome a setback may be to lean into it. In a study entitled, Emotions Know Best: The Advantage of Emotional Versus Cognitive Responses to Failure, participants were asked to complete a simple task. If they succeeded, they were told they could win a cash prize. Alas, the task was rigged so that they all failed. One group was told to imagine focusing on their raw emotional response to losing while the other group was prompted to rationalize the loss. Both groups were then asked to complete a second task. The group that had been asked to embrace their feelings exerted 25% more effort than the rationalizers. Dwelling on the failure and the accompanying unpleasant feelings enabled the “feelings” group to learn from their mistakes and motivated them to work harder the next time.

From childhood, we are told to smile our way through challenges and not to dwell on mistakes, but, as the study shows, leapfrogging over messy unhappy feelings may not always be the best game plan. If we want to learn from our mistakes—at school, at work and in relationships—we need to lean into them.

The relentless emphasis on leading a stress-free-smiley-faced existence may be further exacerbating our discomfort with discomfort. “We live in a period in which there is a tremendous mandate for happiness,” therapist Esther Perel recently told CNBC Make It. These unrealistic expectations set us up for failure and burnout. In fact, despite what the toxic positivity gurus tell us about thinking happy thoughts all the time, a paper entitled When bad moods may not be so bad suggests the opposite: that if we embrace a bad mood, it won’t take such a toll on us.

I think of myself as a positive psychiatrist but that does not mean I think negative emotions should be pushed aside. As Mike observed a few weeks into therapy, “Maybe being the king of moving on isn’t the best strategy if I don’t want to make the same mistake twice.”

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman