Growing up, I was not allowed to use the word “hate.” It was considered a four-letter word in our house. “Dislike” was perfectly fine, but “hate” was verboten. It was my beloved nanny who made this rule, and it applied to everything from broccoli to people.

She believed that hating said more about the hater than the object being hated. In her view, hating something gave it both power and permanence. If I hated my third-grade classmate Stacy for not inviting me to her birthday party, my nanny worried that the sentiment might creep into my everyday existence, coloring all future interactions—or even non-interactions—with Stacy.

If I hated something or someone, she reasoned, it would be virtually impossible to change my mind. But if I merely disliked it? Well then, maybe—just maybe—I might come around. Maybe they would change. Maybe I would. Maybe I would see things differently one day.

Dislike leaves the door open. Hate slams it closed.

For the record, Stacy and I became friends a few weeks later. I still dislike broccoli.

At the very least, my nanny argued, making the decision not to hate kept things in perspective. Disliking something was passive, but hating was active—it was work. She liked to quote Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous words: “I have decided to stick to love… Hate is too great a burden to bear.”

If the word hate rolled off my tongue too easily, she worried it might also take up residence in my heart. And once there, it would become harder to shift.

My nanny believed that words had power, but she also knew they weren’t all-powerful. If someone said something hateful, her advice was simple: don’t dwell on it. She subscribed to that old adage: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” I suspect she would have agreed with the sentiment that words are not violence—only violence is violence. She was a big believer in giving everyone the benefit of the doubt, assuming positive intent, and not judging people in their worst moments.

Every Sunday, Reverend Jeremy Carlson gives this blessing at the end of the service, and it always makes me think of how my nanny approached life and treated everyone she encountered, even those with whom she disagreed:

Life is short, And we do not have much time to gladden the hearts of those who make the journey with us. So… be swift to love, and make haste to be kind.

Please read that twice. Consider committing it to memory.

I call on this message whenever I need to be reminded of the importance of strengthening our connection with those we travel alongside and those whose paths we cross, however briefly.

My nanny’s simple rule about avoiding the word “hate” was never really about vocabulary; it was about perspective. When we catch ourselves reaching for that word, whether about a person, situation, or even Brussels Sprouts, we can pause and ask: What am I really feeling here? Disappointment? Frustration? Fear? Anger?

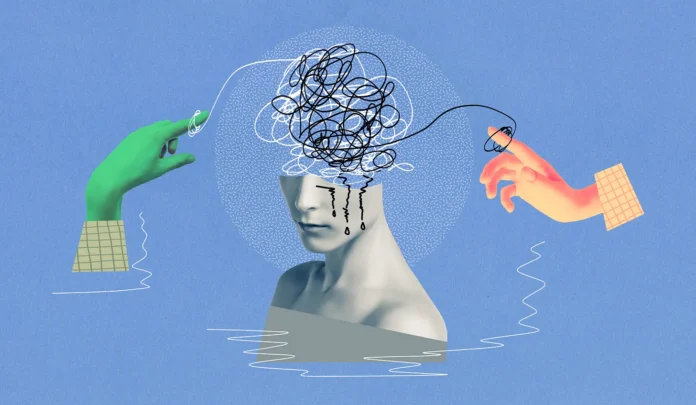

These more specific emotions are not only more accurate, they’re also more manageable. You can work with disappointment. You can address frustration. You can understand fear. But hate just sits there, heavy and immovable, taking up space in your head and heart that could be used for something far more productive.

So try this: For one week, notice when you’re tempted to use the word “hate”—whether in conversation or even in your own thoughts. Replace it with something more precise. See what shifts. You might discover that leaving the door open just a crack lets the light in.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman