It takes a great deal of courage to make an appointment with a psychiatrist. Oftentimes there is a lag between obtaining a therapist’s number and making the call to set up an appointment. I can only imagine how many crumpled up pieces of paper with a psychiatrist’s name and phone number are buried in coat pockets and at the bottom of handbags representing a fleeting moment of intention.

People usually make an appointment to see a therapist during periods of change or transition — in between relationships, in between jobs, in between the known and the unknown. Turning points bring people to the threshold of a therapist’s office. The psychiatrist inquires about symptoms and tries to help them figure out ways to successfully navigate their way through this difficult time. “So, tell me, what is bothering you?” is a common icebreaker.

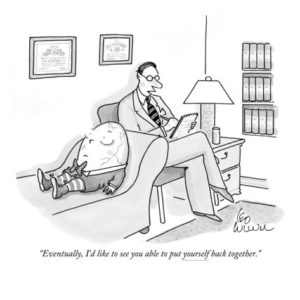

source: Leo Cullum

The focus is on what is going wrong in their lives. After all, that is what brings them in the door. It makes sense.

Or does it? A few years ago a patient, let’s call her Claire, made me question this approach. I had been seeing her for several weeks when she abruptly terminated treatment.

All we do is talk about the bad stuff in my life — what I worry about, what’s upsetting me. I sit in your office and complain for 45 minutes straight. Even if I am having a good day, coming here makes me think about all the negative things.

I never saw her again but her words stayed with me. They stung. She was right. All we did was talk about what was wrong. I had spent years studying damage, deficit and dysfunction in the human mind. It never occurred to me to focus on what was right.

Research suggests it might be time to turn this strategy on its head. Instead of focusing exclusively on repairing a patient’s negative thinking and behavior, therapists may want to consider spending some time building upon their patients’ strengths.

In a study, patients with depression were divided into two groups — half received a classic “deficit-based” treatment that was tailored to work on their weaknesses and symptoms. The other half participated in a strengths-based treatment that targeted the patient’s capabilities and the skills the patient was already good at.

The researchers found that deliberately capitalizing on an individual’s strengths outperforms treatment that focuses on an individual’s weaknesses. This challenges the assumption that we need to fix problems before focusing on anything else.

Today, instead of exclusively troubleshooting with my patients, I also look for bright spots. I inquire about what they are like at their best. I recommend the write down what went well at the end of each day. We explore their strengths and I ask them to use them in new ways. I ask them to consider how they might creatively use that strength to help them navigate their way through a challenging situation. I suggest they look for strengths in others. Thinking about what they admire in someone provides a shift in perspective. Rather than focusing on what they don’t like about the person or their negative qualities, they are reminded of what they appreciate.

We can all benefit from a similar shift in perspective. Catch your child doing something right today. Give a compliment to a friend. Congratulate a co-worker on a job well done. Thank a loved one for a gesture you take for granted. Focusing on what’s right in yourself and others may be just what the doctor ordered.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman