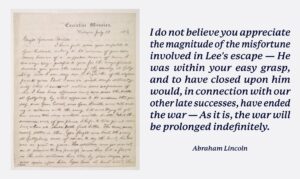

Whenever Abraham Lincoln felt the need to give someone a piece of his mind, he would fire off a harsh letter. Putting pen to paper was his way of unloading his fury. A classic example is the scathing note he penned to General George C. Meade, who he blamed for failing to capture Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg.

Lincoln was “distressed immeasurably” by Meade’s failure but Meade never learned of Lincoln’s immeasurable distress. Instead, Lincoln put the note in a drawer with the label “Never sent. Never signed.” He made a habit of writing “hot letters” but never sending them. It was a way for him to deal with his rage but without the carnage that accompanies spewing unprocessed vitriol. As Maria Konnikova wrote, these unsent angry letters served “as a type of emotional catharsis, a way to let it all out without the repercussions of true engagement.”

The Art of the Active Pause

Learning about Lincoln’s habit is a stark reminder of the value of reflecting on rather than reacting to our emotions. Contrary to cultural pressure to express ourselves, sitting on what is bothering us can act as an emotional windshield wiper, clearing the screen and providing a sharper perspective. In the heat of the moment, it is hard to know the difference between what is urgent versus what is important. As one patient said to me, “Everything Everywhere All at Once could be the title of my life.” Finding ways to press pause and override the itch to react is good for us and good for our relationships.

The impulse to lash out can feel like an imperative–especially with popular TikTok therapists reminding us to always “feel your feelings” and to say what we feel. Plus, with a “send” button at our fingertips, there is little friction between putting our feelings in writing and sending our thoughts out into the world. With an actual letter, finding an envelope and address, plus getting a stamp all take time and time can be a godsend.

It never fails to surprise me how much emotions shift over the course of a week, an hour, or even a night. As the old saying goes, “Everything looks better in the morning.” A patient with a standing appointment on Tuesdays afternoons often tells me how something distressing happens soon after our session–an argument with her partner on Tuesday evening or an issue with a coworker on Wednesday morning–and she has an impulse to tell me about it. But by the time our appointment rolls around a week later, the incident no longer occupies center stage. Whatever felt so earthshaking at the time feels like a minor tremor seven days on.

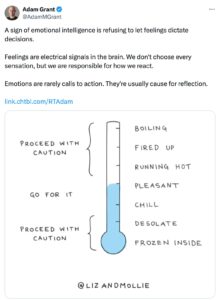

One of the marketing tools of therapy apps is how quickly the therapist responds. Some even offer unlimited 24/7 messaging. Other than in an emergency situation, I am not convinced that having a therapist at one’s fingertips is productive. It deprives the individual of the opportunity to sit on their emotions or even work through the situation on their own. Counter to the questionable advice that masquerades as therapy on social media, waiting it out and not reacting to or listening to one’s feelings is often a better strategy. Not every heated emotional situation is a 5-alarm fire requiring attention or expression or professional intervention. Maybe emotions are getting a little too much airtime in our daily lives. As psychologist Adam Grant pointed out recently on X, feelings are nothing but “emotional signals in the brain.” It is possible that spending less time thinking about how we’re feeling might help us feel better.

There is evidence that the most effective way to deal with our emotions is to take a step back from them. If composing an email but not pressing the send button proves too tempting, consider some other science-backed strategies that might help you gain some perspective such as pretending to be a fly on the wall, or considering what you would tell a friend in the exact same situation, or imagining how you will feel about whatever is going on six months from now. Like writing a letter but never sending it, these self-distancing techniques invite us to step outside of our immediate experience and whirlwind of swirling emotions.

Speaking of swirling emotions, a favorite strategy of therapists who work a lot with teens is to ask them to vigorously shake up a snow globe and then watch the glitter settle. The analogy is clear–their brain is like a churned up glitter jar–all cloudy and hard to see through–but with time, the glitter will fall to the ground and everything will be clearer.

Maybe Lincoln would have enjoyed a glitter jar too.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman