In 1915 a German warship torpedoed the British ocean liner Lusitania off the coast of Ireland, sinking it and drowning almost twelve hundred passengers, including 128 American citizens. A hundred years later my son had to deliver a speech on this attack and its significance to his sixth-grade class. It was a challenging assignment, and he spent stressful weeks rehearsing the presentation, knowing he would be judged by his teachers and peers. His preparation paid off, and when I asked him afterward about the experience, he responded with a smile, “It was really hard, but in a good way.“

Stress, we are constantly told, is unequivocally bad for us. If we want to stay healthy, we are advised to banish it from our lives and avoid it at all costs. From divorce to depression to dementia, we point the finger at stress. If only we had less of it, we are led to believe, we would be happy, healthy, and well-adjusted. Missing from the conversation is how hard and challenging experiences help us grow, and that things can be stressful … in a good way.

New research from the Youth Development Institute at the University of Georgia published in Psychiatry Research found that low to moderate levels of stress can help individuals develop resilience and reduce the risk of developing mental health disorders, like depression and antisocial behaviors. According to the authors, stressful situations and environments prompt individuals to be resourceful and cognitively flexible, and as a result learn strategies and skills that help them overcome adversity and thrive. As they conclude, “Our findings highlighted the role of enhanced cognitive functioning as a mechanism through which low-to-moderate levels of psychosocial stress confer psychological and socioemotional strengthening effects that may help individuals cope with current and future stressors.” Put differently, a certain amount of stress can be psychologically beneficial, potentially acting as a kind of inoculation against developing mental health issues down the line.

The belief that stress is debilitating under any circumstance undermines the ability to cope with life’s challenges and promotes avoidance of uncomfortable but also potentially growth experiences. As the research highlights, adverse experiences can actually make us stronger and prepare us for future uncertainty.

Here is how you can build your stress muscle and get comfortable with discomfort:

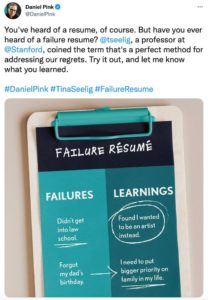

1. Make a Failure Resume

Tina Seelig, Professor of the Practice in Stanford University’s Department of Management Science and Engineering, encourages her students to create a detailed Failure Resume; a full list of all their failures, as well as what they learned from each one of those missteps. Building failure into the learning process normalizes disappointment and frustration. It’s an antidote for perfectionism and puts mistakes into perspective. Challenges are less stressful when seen through the lens of progress and learning. As Seelig notes, “if you want more successes, you are going to have to tolerate more failure along the way.”

Along these lines, talk to your kids about the times you messed up—personally, professionally, academically. Let them know about the goofs, the gaffes, and the stumbles as well as what you do differently as a result. Stepping off the pedestal of perfection will enable them to see challenges as hurdles instead of road blocks.

2. Adopt a Stress-Can-Be Enhancing Mindset

Believing that all stress is toxic can lead to disengagement from resilience building experiences. Indeed a stress-avoidance mentality ignores the reality that elevated levels of stress are normal, and in many ways, even desirable when acquiring new skills. A recent study published in Nature found that students who learn that people’s stress responses are not harmful but instead can fuel performance by helping them persevere and take on difficult challenges were more resilient. The key is to reframe stress responses away from something negative that needs to be feared and tamped down towards recognizing those responses—sweaty palms, a racing heart, for example—as a positive driving force.

3. Get Awkward

Research suggests that if we shift our attitude towards discomfort, seeing it as a sign of progress and something to strive for rather than avoid, we are more motivated to work towards our goals and more engaged in the process. A new paper in Psychological Science suggests that allowing for awkwardness makes people less stress-avoidant and more willing to embrace challenges: “Instead of avoiding the discomfort inherent to growth, people should seek it as a sign of progress. Growing is often uncomfortable; we find that embracing discomfort can be motivating.” Across a range of situations, including improv classes, expressive journaling, as well as learning about challenging topics such as COVID-19, opposing political viewpoints, and gun violence, people who were invited to embrace discomfort persisted longer, engaged more, and were more curious.

Psychiatrist Richard Friedman, who runs the mental health services for Weill Cornell Medicine of Cornell University in New York, has voiced concern that the emphasis on wellness today is creating unrealistic expectations that everyone should be smiling and stress free at all times. “Though I can’t prove it,” Friedman wrote, “I suspect that my generation suffered less burnout than current students for the simple reason that we expected to have a rough ride.”

Each year Friedman greets incoming first-year medical students by telling them, “These next four years will be exciting and challenging and stressful … It’s entirely natural to feel anxious, overwhelmed at times, and exhausted. In fact, it’s evidence you are alive and engaged in your work.”

We feel stress because we care and because we’re striving. Poet David Whyte describes this succinctly: “In romance, in parenting, and in our professional lives—when we’re fully committed and deeply engaged, we get hurt, feel frustration, upset. And that’s not a bad thing. It means you are sincere and committed.“

Bottom Line: Things can be hard and stressful … but in a good way.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman