The number, frequency, and urgency of decisions that demand our attention on a daily basis are exhausting. Here are 5 strategies that might help.

Cream or Milk?

Do you want fries with that?

Should I bring an umbrella?

Our days are essentially one decision after another. The number, frequency, and urgency of decisions that demand our attention on a daily basis are exhausting. Decision-making has gotten even harder during the pandemic. As one patient told me recently, “It took me 10 minutes to decide if I should give my dog a bath today or tomorrow. I overthink everything. Every decision feels momentous.” Another told me that she and her partner took so long deciding what movie to watch they gave up after an hour of watching trailers. The idea of committing to anything feels daunting.

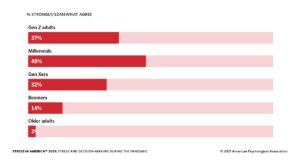

Increasing numbers report “decision paralysis” over minor and relatively inconsequential decisions. Nearly one-third of adults (32%) said sometimes they are so stressed about the coronavirus pandemic that they struggle to make basic decisions, such as what to wear or what to eat. Millennials (48%) were particularly likely to struggle with this when compared with other groups (Gen Z adults: 37%, Gen Xers: 32%, Boomers: 14%, older adults: 3%).

Sustained stress drains our cognitive resources, and the uncertainty of the pandemic has left many feeling emotionally exhausted and overwhelmed. Our brains are buckling under an endless stream of information, making it even harder to make good choices and focus our energy productively.

These days, the risks and benefits of participating in basic activities require ongoing assessment and evaluation. From attending social gatherings to going to a restaurant to taking public transportation, we have to ask ourselves, “Should I or shouldn’t I?”

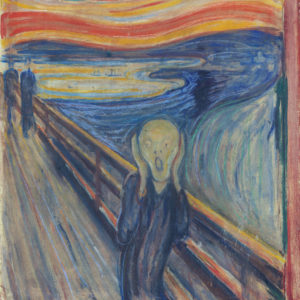

Cognitive overload makes it challenging to process, sort, and prioritize data. As a friend put it recently, “Every decision makes me feel like Edvard Munch’s ‘The Scream.’ I just want to hold my head and shout ‘I don’t know.'”

If you are experiencing decision paralysis, here are 5 strategies that might help.

1. Stick to a routine

Establishing a predictable routine will help keep minor decisions at a minimum. Wash the dog on Sundays. Call your grandmother on Fridays. Schedule a walk with a friend on Saturdays. Structure leaves less wiggle room for indecision. Plus, research from the University of Southern California found that establishing healthy habits makes us more likely to default to them during periods of stress. For instance, participants who regularly ate oatmeal for breakfast during the semester were more likely to eat a healthy breakfast during exams. Students who ate unhealthy breakfasts during the semester — such as pastries or doughnuts — ate even more junk food during exams.

2. Be your own Choice Architect

Instead of depleting valuable cognitive resources to guide you through each and every decision, eliminate unnecessary choices. Steve Jobs famously wore a black turtleneck every day so he didn’t have to waste time thinking about what to wear. I have a friend who always orders the special in a restaurant so he doesn’t have to bother with the endless options on the menu. As your own choice architect, design your surroundings to promote choices that reflect your values. Fill your refrigerator with healthy options to spare, turn your bedroom into a sleep sanctuary, and place your sneakers by the front door to remind you to go for a walk. Making it harder to choose behaviors that don’t align with your values makes it easy to choose behaviors that do. Eliminate vitality draining options. If you throw out the candy bar in your desk drawer, you won’t waste time thinking about whether or not you should eat it.

3. Aim for good enough

Instead of investing substantial time and effort mulling over the details of every option, aim for good enough. Research in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that Maximizers, people who agonize endlessly over decisions, experience more regret and lower levels of happiness than Satisficers. If you are exhibiting Maximizing tendencies, consider the following exercise. Over the next week, make one choice every day that is “good enough.” For example, if deciding what to cook for dinner, throw together what you already have in the fridge. If in need of a new toothpaste, close your eyes and pull one off the shelf. Later in the day, reflect on why this choice was a fine choice as well as the benefits of deciding without relentless deliberation.

4. Remember to HALT

If decision fatigue is depleting your energy stores and willpower, don’t forget to HALT.

HALT stands for:

If you are experiencing any of the above, you may be vulnerable to making impulsive or suboptimal choices. The key is to recognize how these states might influence your decision-making capacity and to press pause before rushing into a decision you might later regret. Next time decision paralysis kicks in, ask yourself: Am I hungry, angry, lonely, or tired? Eating a snack, taking a walk, calling a friend, and getting a good night’s sleep might work wonders. As the old saying goes, don’t make a permanent decision because of a temporary emotion.

5. Perform a pre-mortem

Doctors perform a post-mortem when a patient dies to figure out the cause of death. A pre-mortem is the hypothetical opposite. Instead of waiting for “the end” to figure out what went wrong, a pre-mortem is a hypothetical exercise that you perform before a decision has been made. The idea is to imagine yourself in the future and that the decision you made did not turn out well. For instance, perhaps you are considering leaving your job. The upsides are obvious to you. To make sure you aren’t missing anything, fast forward in your mind three months and imagine that you are bored, lonely, and concerned about finances. By forcing yourself to imagine scenarios that turn out to be sub-optimal, you can pick up. blind spots in your thinking according to psychologist Gary Klein.

Bottom line: Don’t be a squirrel when it comes to making decisions.

I wish you all the best,

Dr. Samantha Boardman